Are you wondering what Blockchain Development is and how it works? Well, the solution rests here.

According to The Future Market Insights Inc . records that the Blockchain Market is estimated to be valued at USD 20.0 billion in 2025 and is projected to reach USD 376.4 billion by 2035, registering a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 34.1% over the forecast period.

Thus, this article aims to cover what blockchain development is, its choices, and hidden constraints, followed by blockchain app development services and understanding how it actually works.

Key Takeaways

- What blockchain development actually includes today

- Choosing a blockchain model based on real constraints

- Smart contract design beyond basic correctness

- Off-chain architecture is where most complexity lives

- Security thinking that goes past audits

- Regulatory and compliance considerations that shape design

- Development workflows that scale past the first release

Blockchain development is no longer a single discipline. It includes protocol interaction, application logic, infrastructure, and operational processesall in one.

Treating it as “writing smart contracts” creates blind spots that surface late and expensively, creating losses.

At a practical level, modern blockchain development includes several layers that evolve at different speedsand characteristics.

The base protocol changes slowly and values stability. Whereas, Application layers move faster and absorb most feature pressure. At the same time, Infrastructure sits in between and often becomes the bottleneck during growth.

Key components teams end up owning:

Each layer brings its own failure modes. Ignoring one because it feels “non-blockchain” leads to brittle systems that often look decentralized on paper but fail operationally because of these factors.

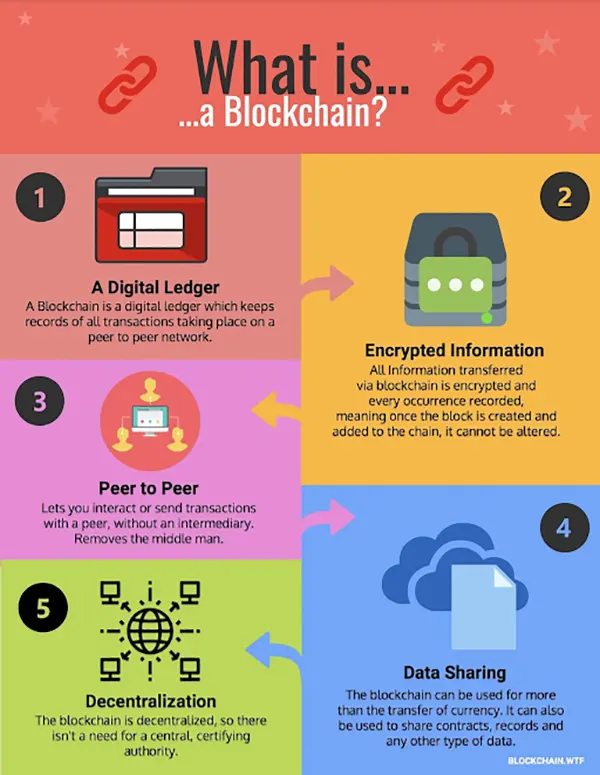

The infographic includes further details of what a blockchain actually is :

Public, private, and consortium blockchains are often compared, yet the discussion usually stops at ideology.

In practice, the choice is driven by operational constraints and long-term governance more than philosophy, which means planning appears different in practice than on paper.

Public chains impose strict limits on throughput and cost predictability.

Gas fees fluctuate, and execution order may not be fully under your control. These factors shape the application design.

Public chains fit best when shared state matters. Tokenized assets, open marketplaces, and protocols that benefit from third-party integration gain leverage from openness.

Private chains trade openness for control. They allow predictable performance, easier compliance alignment, and concentrate trust, which shifts risk from protocol failure to operator failure.

Permissioned systems often succeed when they mirror existing governance structures and fail when teams expect them to magically remove coordination costs between organizations.

Consortium chains sit between public and private models. They distribute control across known parties while keeping participation gated.

Before choosing this model, teams should pressure-test non-technical questions like :

The table below summarizes how these models differ in practice.

| Aspect | Public blockchain | Private blockchain | Consortium blockchain |

| Access control | Open participation | Single operator | Restricted to members |

| Cost predictability | Variable transaction fees | Fixed or negotiated | Shared operating costs |

| Governance | Protocol-level, slow changes | Centralized decisions | Multi-party agreements |

| Composability | High with external apps | Limited by design | Moderate within network |

| Operational risk | Network congestion | Operator failure | Coordination failure |

Smart contracts are immutable by default, which makes early design choices unusually durable. Correctness is necessary but insufficient. They should also be adaptable, observable, and economical over time.

Upgradeable contracts reduce risk early but introduce governance complexity in the long run.

Proxy patterns allow logic changes, yet they create trust assumptions that users may not expect.

A useful rule is to scope upgrades narrowly, as Core asset logic benefits from stability.

Fun Fact

In 2010, someone in Florida paid 10,000 bitcoin for two pizzas (worth then about $40). It is generally accepted as the first commercial bitcoin transaction.

Gas economics influence who can use the system and who can’t. Designs that look elegant in code can exclude users during high-fee periods.

Teams that manage this well tend to:

Ignoring gas early often forces rushed refactorings later, sometimes requiring contract migrations that fracture state, which is an involuntary condition.

Once deployed, smart contracts don’t log like traditional services. Events can help, but they also require foresight. Without structured events, diagnosing failures becomes forensic work.

Experienced teams design events alongside functions. They log intent and outcomes, not just errors. That discipline pays off during audits and incidents.

Despite the focus on decentralization, most blockchain products rely heavily on off-chain components.

These systems handle indexing, caching, user sessions, and integrations, and reintroduce familiar engineering challenges.

Blockchains aren’t databases optimized for reads. Querying the historical state directly from nodes doesn’t scale for user-facing applications. Indexers are seen to be bridging that gap, but they create consistency questions.

A common pattern is eventual consistency with explicit status indicators. Users see pending states until on-chain confirmation arrives.

Integrations with payment processors, identity providers, or enterprise systems require careful boundary design. Oracles and relayers become critical infrastructure in such situations.

Good designs limit what external inputs can influence. They also include circuit breakers.

Off-chain services need uptime, alerting, and capacity planning. Blockchain doesn’t remove those responsibilities but rather adds irreversible side effects when automation misfires.

Teams that succeed invest in dry-run modes and staged rollouts. Which simulates transactions before broadcasting them.

It is this practice that catches configuration errors that would otherwise be permanent.

Audits catch many issues, but they’re just snapshots in time. Real security emerges from continuous threat modeling and operational discipline.

Threat models should evolve as value and visibility grow. Attackers follow incentives. A contract holding negligible value won’t attract the same scrutiny as one that secures a large pool.

Practical threat modeling considers who benefits from failure. Phishing and social engineering often cause more losses than technical exploits.

Complex systems fail in complex ways. Each feature adds state and interaction surfaces. Whereas Simpler contracts with fewer branches reduce both bugs and cognitive load during reviews.

This doesn’t mean minimal features. It means deliberate scope control where features can live off-chain.

Incident Response in an Irreversible World

When something goes wrong on-chain, options are limited. Pausing mechanisms help sometimes, but can undermine decentralization narratives at times. Clear policies matter more than perfect tools.

Teams prepare by defining response thresholds. They decide in advance when to pause, upgrade, or accept loss. Making those calls under pressure leads to inconsistent outcomes.

Regulation affects blockchain development unevenly. Some applications feel little impact. Others are constrained from day one. Ignoring this reality doesn’t make it disappear.

Regimes like GDPR clash with immutable storage. Even hashed data can be problematic if it remains linkable.

A safer pattern keeps personal data off-chain. On-chain references point to revocable records. That approach aligns better with evolving interpretations of data rights.

Applications touching value flows face scrutiny around custody, reporting, and controls.

Note- Blockchain’s transparency helps, but only if systems are designed to surface the right information.

Clear separation between user funds and operational accounts simplifies audits. So does deterministic transaction logic that produces predictable outcomes.

Rules vary by region and change over time. Hard-coding assumptions about allowed users or assets creates rigidity. Configuration-driven controls adapt more easily.

Teams that anticipate judicial fragmentation avoid embedding policy deep in smart contracts. Instead, they leave room for off-chain enforcement where updates are feasible.

Early blockchain projects often rely on heroic efforts and informal processes. That approach collapses as teams grow and stakes rise.

Unit tests alone don’t capture cross-contract interactions or timing issues. Integration tests and simulations reveal behaviors that static analysis misses. Making the testing strategies go beyond confined setups.

Effective test setups usually include:

Skipping these saves time early, but multiplies risk later.

Blockchain expertise concentrates easily. A single engineer may understand the full system. That’s efficient until they leave or burn out.

Spreading knowledge requires documentation and shared reviews. But it also means resisting over-customized tooling that only one person can maintain.

Blockchain applications don’t reach a clean “done” state. Dependencies evolve. Networks fork. Tooling deprecates. Planning for maintenance avoids panic upgrades.

Teams that plan budgets for ongoing support treat blockchain as infrastructure, not a campaign. And it is this framing that changes how decisions get made.

Blockchain development today is less about novelty and more about disciplined engineering under unusual constraints.

Teams that focus on real constraints outperform those chasing abstractions.

They think in layers, balance on-chain and off-chain responsibilities, and treat security and compliance as ongoing practices turn blockchain from a risky experiment into a dependable part of the stack.

Private blockchains are deployed either within an organization or shared among a known group of participants. They can be limited to a predefined set of participants.

Ethereum is a group of incredibly smart individuals who have developed the next generation of cryptocurrency. The Ethereum project involves a large single network (much like Bitcoin), and runs on a cryptocurrency that can be mined (Ether).

The “block” in a blockchain refers to a block of transactions that has been broadcast to the network. The “chain” refers to a string of these blocks.

A “block” in the Ethereum blockchain refers to a block of transactions that has been broadcast to the network.